TEXT

Texile Art for better or for worse

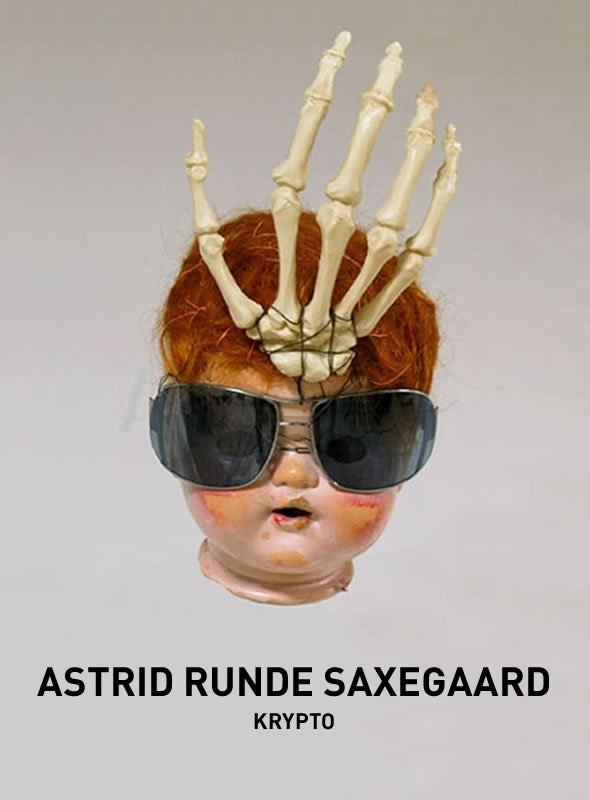

When contemplating Astrid Runde Saxegaard’s artistic universe, we find ourselves in limbo between what is generally recognisable on the one hand, and what is disturbingly alien on the other. In this way, we are drawn into a mental landscape of associations that give rise by turns to well-known and often humorous memories of a common heritage or our own childhood and then to underlying, far more disconcerting mental pictures. This to and fro between the good and the bad is latent in her works and makes us actively question whether it is wise to expose ourselves to Saxegaard’s art with our emotional defences down. For there is a definite possibility that partially suppressed stories from our own past may be turned inside out. Nevertheless, we hesitatingly accept the invitation to enter her tempting, surrealistic world of art, where dark shadows lie in wait for us.

Background: a break with tradition and “lived life”

Saxegaard studied at the State College of Handicrafts and Applied Art (now the Oslo National Academy of the Arts) and completed her studies by taking a master degree in textile art in 1996. While a student, a study tour to Iceland was to prove an important learning experience. Her meeting with the people of this land of sagas and with the nature and distinctive cultural stamp of Iceland gave Saxegaard much of the inspiration that has shaped her further, in-depth study of the wide potential that lies in the textile medium. In brief, the time Saxegaard spent on Iceland led her to incorporate random objects of “lived life” into new, textile-based constellations. Though her interest for using objects in combination with textiles only emerged gradually during the years immediately following her graduation, this approach has matured, and Saxegaard now increasingly uses it as a deliberate artistic strategy. Today, she is not so much concerned with randomly found objects, but rather with a meticulous search for objects that seem to have the right, immanent quality.

In contrast to the traditional perception of textile art as weaving and printing on material, Saxegaard’s artistic activity must be categorised as belonging to a wider and more experimental field, in which objets trouvés, or found objects, form the nucleus of her artistic idiom.

In the main, Saxegaard’s works consist of large-scale wall textiles, which can usually be regarded as assemblages since three-dimensional elements are added to the two-dimensional surface. In addition to wall-based works, she also creates installations and object art. In these works, she often employs other media such as drawings, photographs, videos and fragments of text. Whereas her earlier works often possessed a clearly recognisable use of symbols, with hearts and crosses as a recurring theme, Saxegaard’s more recent works contain a more ambiguous and imaginary symbolism. This change of direction reveals Saxegaard’s continual development as an artist; her works’ use of media and interpretative potential are given a freer rein and sharper sting.

Saxegaard’s use of materials and artistic process: beauty in ugliness

Saxegaard finds her raw materials and bases her artistic ideas on discarded objects and textiles, such as odd socks, a pink dressing gown of padded nylon from the 1960s, a worn boa or a broken doll. Things that we normally define as outdated, worn, old-fashioned and kitschy are considered as valuable findings by this artist. Her instinct as a collector reveals a sensitivity for these objects’ inherent stories of “lived life”. Her interest in their authenticity and tactility - that something purely physical has been used and has had a function in real life - is significant. At the same time, her choice of outdated textiles and objects as a medium transcends pure nostalgia, since her re-use of such objects can also be seen as a protest against our commercialised society’s “use and discard” mentality. Collecting gaudy, over-decorated textiles and other so-called “tasteless” things is for Saxegaard also a facet of her somewhat ambivalent relationship to the redefinition of aesthetics. Indeed, she herself describes many of the things to be found in her atelier as so ugly that they arouse a real feeling of physical discomfort in her. But challenging her own aesthetic tolerance in this way generates the ideas that finally find expression in her art.

Creating new, visual expressions by means of found objects is a demanding and meticulous process. The conceptual process must therefore be regarded as equally important as the completed work. Saxegaard’s ideas come to life through an intuitive and laborious process whereby textiles and objects are assembled and processed in such as way that new and unexpected stories emerge. By trial and error and experiments, Saxegaard questions what effects the various different constellations bring about. What happens when you cut the back off an old garden chair of cast iron? What stories can the worn-out seat and the rusty, wobbly chair legs tell as this piece of garden furniture is transformed into a pink pouffe with a clitoris motif embroidered on its cushion? What happens when an orange camping tarpaulin from the 1970s is used as a present-day tablecloth, or when a soiled head of a doll is wrapped in upholstery padding? And last but not least: what do we experience when these fragments of “lived life”, cultural references, different stylistic periods and social codes are juxtaposed in one and the same installation?

Understanding content: disquiet, taboo and existentialism

Saxegaard’s works of art can be described both as cacophonic surrealism and humorous tableaus, but on closer examination, most of them contain a silent narrative of sombre power. They focus on familiar issues about personal experiences and interpersonal relationships in a wide perspective, for instance the confrontation between high and low culture, dashed expectations between different generations in the family, a dissociation with upholding cultural heritage, the expression of taboo subjects and the overriding problem of social-political identity. The well-known literary critic Barbara Johnson has claimed that colours, shapes, motifs and figures act as “Trojan horses” that can give rise to quite different associations than the artist herself was aware of. Saxegaard’s many-faceted works can in this connection be interpreted as the bearers of innumerable and varied stories, depending on which references the works arouse in the observer.

One of the iconographic leitmotifs of Saxegaard’s work is her way of combining things that are familiar and safe with things that produce an underlying disquiet. One of the leading creators of this form of psychological dualism in the field of textile-based art is the French artist Anette Messager (born 1943). As with Messager, Saxegaard’s art bears witness to a similar and recurring interest for distorting the meaning of the works from something apparently recognisable to a different and more loaded perception of reality. Just as Messager, by means of seemingly disarming and childish rag doll installations, poses questions about incendiary themes such as the physical and psychological oppression of children, Saxegaard produces similar contrasts by her critical reflections on gender issues and the sexual emancipation of women. Her early work Kaleidoskop (1997) can serve as an example of how dichotomies such as security/insecurity and freedom/oppression are juxtaposed to produce a state of contrast and friction. The installation, which from a distance gives the impression of being a meticulous woman’s wardrobe from the 1950s, turns out, on closer examination, to consist of lacy underwear, nightdresses and duvet covers that have been altered to form large female breasts and male genitals. The objects, which are squeezed into a wardrobe, hang like limp, ironic relics of postmodernism’s gender debate. In a partly humorous way, Saxegaard transforms harmless and familiar things into inflammatory issues, with the result that the life and sexuality of women are once again up for debate.

The choice of textiles as a medium, and a gender-related approach to content, are characteristics common to most of Saxegaard’s works. This links her artistic activity to feminist-orientated art, in which sexual emancipation and gender issues play an important role. Nevertheless, Saxegaard’s investigation into taboo areas in familiar, cultural contexts and the interpretative framework of her works are more personally motivated than the result of a generally politically feminist attitude. A similar attitude can be found in the works of the English artist Tracy Emin (born 1963) who is known for using her own life and experiences as the raw materials of her art. Her ground-breaking installation My Bed (1999), which consists of Emin’s own bed and the trappings of her bedroom, reveals extremely personal experiences such as loss, illness, fertility, conception and death. In Saxegaard’s case, a personal, but not necessarily private motivation, is an equally core aspect of her art. In this way, the artistic idiom is derived from her own experiences – things that the artist herself has felt and lived through. The overriding concept of giving second-hand textiles and other objects a strongly symbolic power seems to be a common feature of both Emin’s and Saxegaard’s oeuvre.

The use of mirrors is another recurrent feature of Saxegaard’s installations. A mirror can be perceived as an effective metaphor and a reminder that the art we are witnessing in fact is about each and every one of us. Any attempt at distancing oneself is frustrated since our own reflection appears as a real and physical part of the work – the observer and the work merge and become one. However, the use of mirrors is first and foremost an important, symbolic device for the artist herself in that her own experiences from her childhood environment in Northwest Norway appear as both underlying and exposed points of departure for her works. Through their references to homely values and moral norms, her works reflect the need for an examination, emancipation and definition of her own, independent ego. At the same time, the themes and issues contained in the works can be said to be universally valid since they legitimate every individual’s need for a personal definition of their own development. In this connection, it may be relevant to draw a parallel with another contemporary artist, also with roots in Northwest Norway, who is known for creating art with references to his own background and origins: Per Inge Bjørlo (born 1952). Whereas Bjørlo creates a masculine and sometimes brutal idiom by using for example crudely weldered metal and splintered glass, Saxegaard’s use of materials results in a softer and more feminine look. The difference between their artistic idioms points to the fact that Bjørlo appears to be making an explicit and sometimes quite violent break with his own social and cultural heritage, whereas Saxegaard seems interested in posing more indirect, searching and philosophical questions about the same theme. In other words, Saxegaard makes no judgements. Her works present no clear-cut conclusions. Instead, they reveal by means of intricate codes and symbols stories that at once unveil and conceal their intended meaning. In this way, the works are both complex and open and they leave it up to the observer to make any potential or definite conclusions.

Who you are, what you are and where you come from are parameters that make their mark on everybody’s lives for better or for worse. Saxegaard’s works pose questions about the principles of existentialism and it is this that makes them strong and universally relevant.

Astrid Runde Saxegaard’s works will be showing at the exhibition “KRYPTO” at the Norwegian Textile Artists’ gallery SOFT from 20th October to 9th December 2007.

Janicke Iversen

Art historian